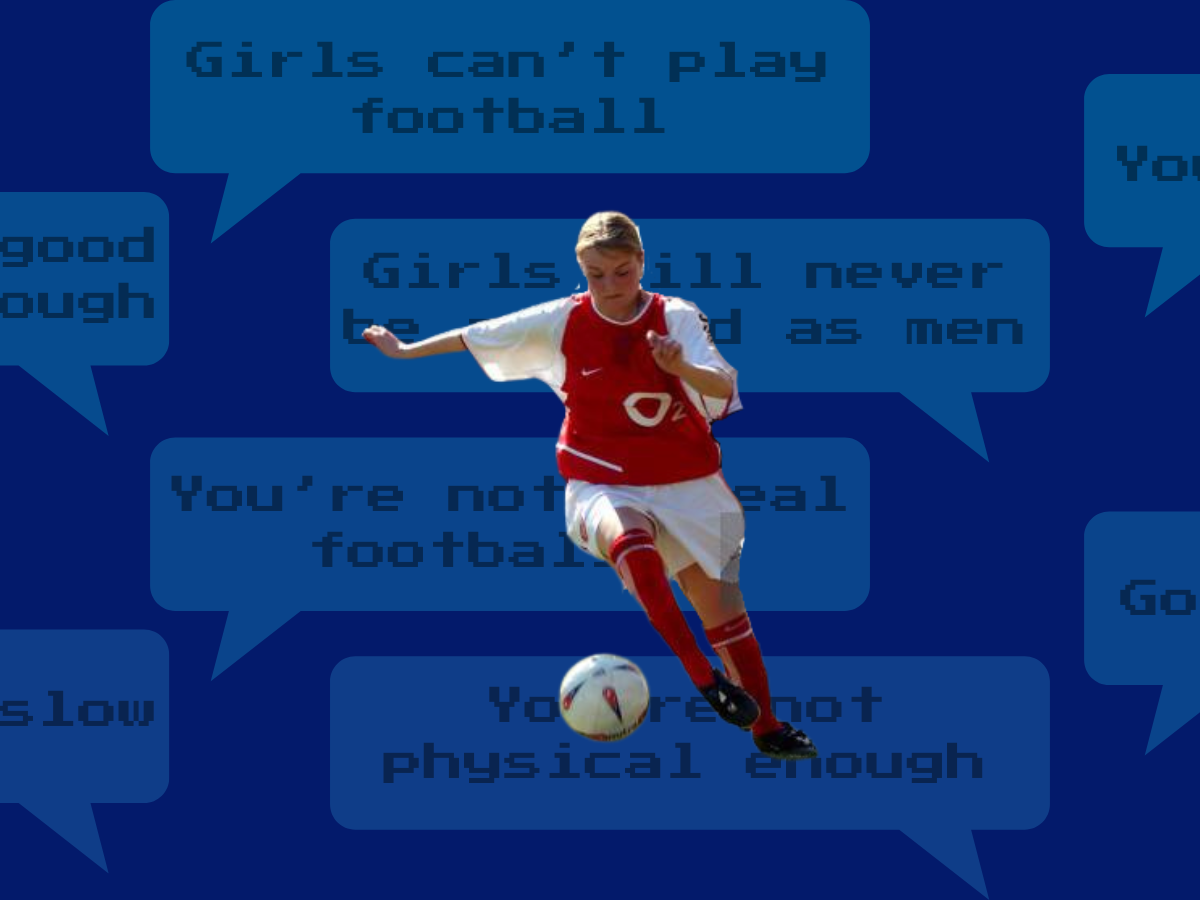

Former Arsenal and England striker Ellen Maggs received her fair share of abuse in her career, but admits that the situation has taken a drastic turn for the worse in recent years, especially in the women’s game.

“I played in a time where women’s football wasn’t really valued at all. A handful of those who came to watch were there to laugh about women’s football and you would hear the comments whilst you were playing. I never let the words affect me but I know it did affect some of the girls we were playing with and against.” said Maggs.

An investigation conducted by FIFA concluded that one in five of the players who appeared in the 2023 Women’s World Cup received discriminatory, abusive or threatening messages, and were 29% more likely to be targeted by this abuse than those who played in the 2022 Men’s World Cup.

“I can’t imagine how these professional players now, like Lauren James, who get an unbelievable amount of abuse on social media would deal with it. I can’t even imagine where you would start to train yourself to deal with it.” said Maggs.

Maggs, now the owner of a football club and a coach herself, believes that this culture of abuse in football begins at the grassroots level, and has seen it first hand. “The more I’m involved in football the more I realise how little decisions that a coach makes at grassroots level can affect a child in a way we don’t even realise. You see coaches in non-competitive games approaching it like a Champions League final and kids are getting screamed at.”

Abuse towards players on the pitch has also become a growing issue in the men’s game. It wasn’t until after he hung up his boots that former Manchester United and England Star, Michael Carrick, opened up about how he suffered depression after a mistake he made in the 2009 Champions League final loss to Barcelona, which led to Samuel Eto’o prodding the ball past Edwin van der Saar to give the Spaniards the lead.

“As a footballer, you are expected to be that machine that just churns out results after results, performance after performance.” Carrick says, “You are paid well and you play for a big club so why can’t he be good every week? It’s just not like that. It’s not easy to do that and it’s easy to forget that. There could be all sorts going on that you don’t know about.”

Michael Carrick retired as a five-time Premier League victor and a Champions League winner, receiving 34 Caps for England.

“It felt like I was depressed. I was really down. I imagine that is what depression is.” says Carrick, “I beat myself up over that goal. I kept asking myself, ‘why did I do that?’ and then [my depression] snowballed from there. It was a tough year after that. It lingered for a long time.”

Carrick mentioned how his depression clouded over his 2010 World Cup campaign with England, which has been his dream since he was a little boy, which shows how his career was derailed by the standards that he had set himself as a result of media scrutiny and expectation.

It was these same pressures that led English football veteran Aaron Lennon to be sectioned in 2017 whilst playing for Everton amidst concerns over his well-being.

There are almost 4000 misconduct offences in youth football by adults according to research done by the Football Association. In recent years, more and more notable footballers have stepped forward to express their grievances, paving the way for others to do so in the future.

Top clubs have hired counsellors, mental health charities are becoming increasingly involved in the sport, and social media websites have developed new software to filter hateful comments so that players don’t see them.

Related Content